Nevertheless it’s an enjoyable read, and never feels like the chore that the previous book did. A couple of the vital clues are telegraphed heavily – much as happened with Hallowe’en Party two years earlier – and as a result it’s quite easy to work out not only whodunit but their modus operandi. There are a few moments that rather require a suspension of credibility – but it’s not as bad as some, from that perspective.

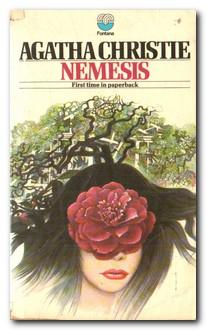

There are a number of hark-backs to previous books, both thematically and in the re-use of characters but it succeeds in being a good story, with a central plot puzzle that unfolds organically and ends with an eerie, exciting denouement. With similarities to other works where a crime from the past is investigated in the present, there are some extremely good passages of writing, and some difficult subject matter is treated with delicacy and sensitivity. But whilst Nemesis is far from her best work, it’s even further from her worst. The full book was first published in the UK by Collins Crime Club in November 1971, and in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company later that year.Īfter the massive disappointment of Passenger to Frankfurt, one might have thought that Christie had run out of good stories and her usual slick storytelling style. Nemesis was first published in the UK in seven abridged instalments in Woman’s Realm magazine from September to November 1971, and in Canada in two abridged instalments in the Star Weekly Novel, a Toronto newspaper supplement, in October 1971.

The book is dedicated to Daphne Honeybone, who was Agatha Christie’s private secretary after Christie’s death in 1976, she continued working for Max Mallowan. But are all the other passengers genuine, and what crime will Miss Marple stumble upon? As usual, if you haven’t read the book yet, don’t worry, as always, I promise not to reveal what happens and whodunit! Piqued with curiosity, Miss Marple accepts his challenge, which results in her taking a coach tour of Famous Houses and Gardens of Great Britain. He asks her to investigate a crime but gives no other indication of what it is or how she should do it. In which Miss Marple is contacted “from beyond the grave” (via a solicitor’s letter, not a Ouija board) by the late Mr Rafiel with whom she worked in A Caribbean Mystery.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)